The state of Maharashtra has undertaken significant strides in institutionalizing social audits

as a mechanism to enhance transparency, accountability, and participatory

governance—especially in the implementation of rural welfare schemes such as the

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). Social

audits function as participatory tools, empowering citizens to assess the delivery and

effectiveness of government programs and ensure public resources are used responsibly.

The Maharashtra State Society for Social Audit and Transparency (MS-SSAT) was formally

established in January 2018 to operationalize the social audit process as per the mandates

under Section 17 of the MGNREGA Act. However, the older Directorate of Social Audit

under the Employment Guarantee Scheme (EGS) Department still operates in parallel,

leading to administrative overlaps and delayed transfer of responsibilities. This dual

structure, along with a shortage of trained personnel and inadequate financial autonomy,

continues to hinder the efficacy of Maharashtra’s social audit system.

Audit Process and Coverage

In Maharashtra, the social audit of one Gram Panchayat (GP) typically spans five days,

involving approximately three Village Resource Persons (VRPs), adjusted based on

habitation size, terrain, and job card numbers. Audits are conducted simultaneously in 20

GPs per block, supported by 60 VRPs, 5 Cluster Resource Persons (CRPs), one Block

Resource Person (BRP), and overseen by a District Resource Person (DRP). State

Resource Persons (SRPs) monitor multiple DRPs and ensure coordination with district

officials. VRPs are required to stay in the GP during the audit, lodging in public buildings like

GP offices or schools. While audits are meant to be held biannually in every GP, actual

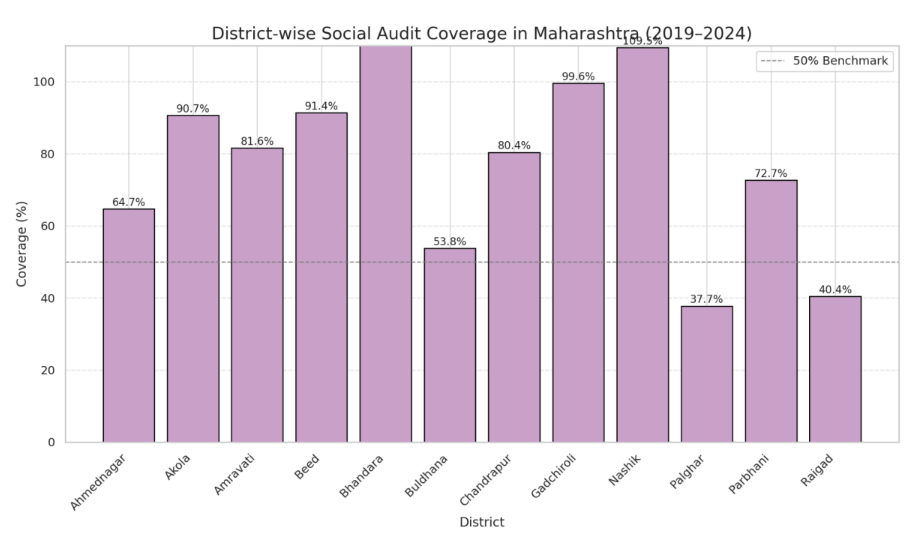

coverage has been inconsistent. Between 2019 and 2024, Maharashtra’s 27,882 GPs saw

highly uneven audit frequencies across districts. For instance, districts like Gadchiroli and

Nashik reported high audit coverage, whereas others such as Palghar, Parbhani, and

Raigad witnessed near-zero activity in recent years.

Graph 1: District-wise Social Audit Coverage in Maharashtra (2019-2024)

Data reflects total audits conducted per year; repeated audits of the same GP may inflate

total count.

The average cost of conducting a social audit per GP is approximately ₹15,000, which

covers the logistics, personnel honoraria, and documentation. However, inadequate

resource allocation and limited staff capacity remain persistent challenges.

Audits have revealed numerous irregularities, including missing saplings, fake invoices,

incomplete works, and payments made to non-workers. Unfortunately, financial

misappropriation often goes unquantified, and delays in payments—especially for skilled

labor—remain common grievances.

Follow-up mechanisms have been formalized through monthly review meetings with District

Collectors. However, many of these efforts are constrained by delayed submission of Action

Taken Reports (ATRs), non-cooperation by local officials, and poor integration with grievance

redressal systems.

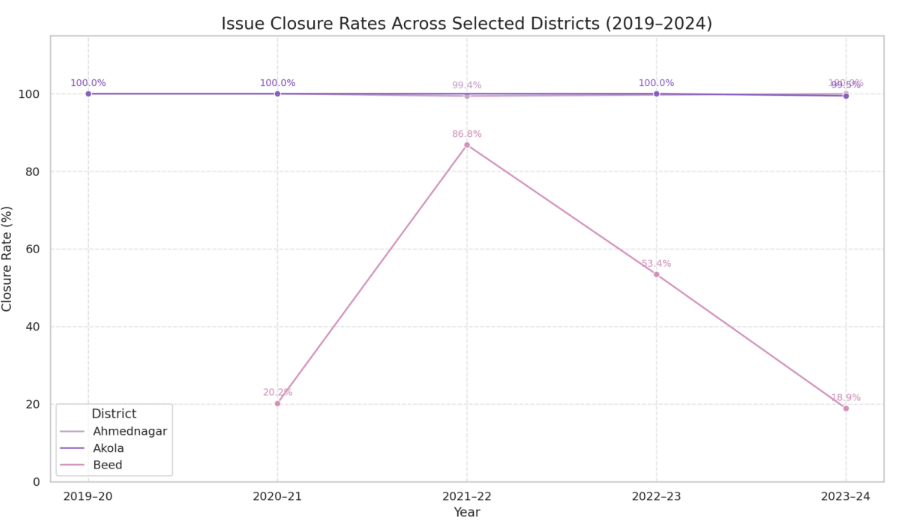

From 2019 to 2024, despite thousands of issues being reported, the issue closure rates

varied dramatically. Districts like Ahmednagar and Akola demonstrated near-perfect

follow-up, while Beed had a closure rate of just 18.89% in 2023-24, reflecting a troubling gap

between detection and resolution.

Graph 2: Issue Closure Rates Across Ahmednagar, Akola and Beed (2019-2024)

While the primary focus has been on MGNREGS, Maharashtra has also piloted audits for

other welfare programs like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) and the National

Social Assistance Programme (NSAP). These initiatives indicate potential for expanding the

scope of audits to a broader array of schemes, though scaling efforts are still nascent.

Key Challenges and the Way Forward

The state’s social audit system faces multiple systemic hurdles: lack of autonomy for

MS-SSAT, poor integration of findings into policy reform, delayed recruitment of trained

personnel, and insufficient funding. Furthermore, the dependence on VRPs—often

undertrained and inadequately supported—compromises the quality of audits.

To strengthen the social audit system, Maharashtra can:

● Streamline institutional structures by formally consolidating MS-SSAT’s authority.

● Invest in capacity building and training for audit personnel.

● Ensure transparent publication of findings and actionable follow-ups.

● Expand audits beyond MGNREGS to other critical rural and social welfare programs.

In conclusion, while Maharashtra has taken commendable steps in embedding social audits

into its governance framework, much work remains. With stronger implementation, greater

political will, and community engagement, social audits can evolve into powerful tools for

grassroots democracy and inclusive development.

First Author- Gargi Phadnis

Second Author- Ananya Sonavane