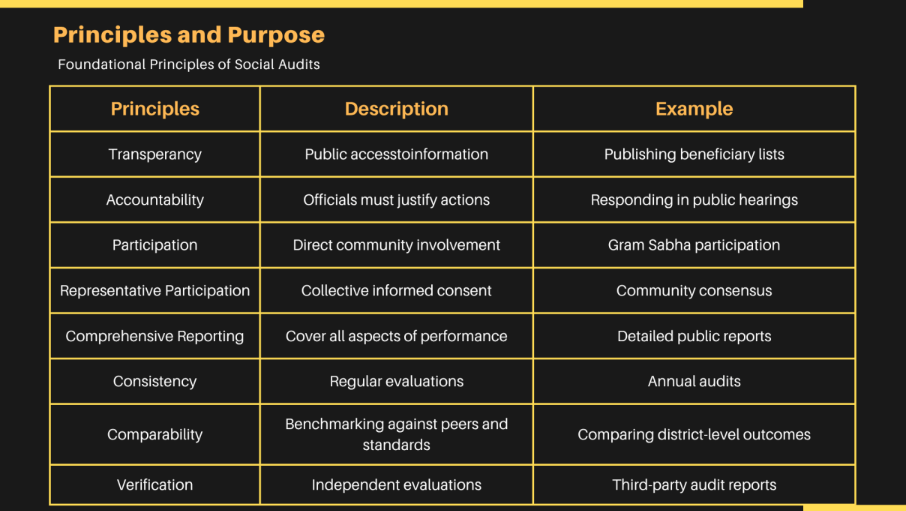

A social audit is a participatory evaluation process where the performance of a public

scheme, policy, or organization is assessed through the combined efforts of the government

and the people—particularly those affected by the initiative. Unlike traditional audits that

focus on finances, social audits prioritize transparency, accountability, and social impact,

ensuring that governance aligns with ethical standards and community welfare.

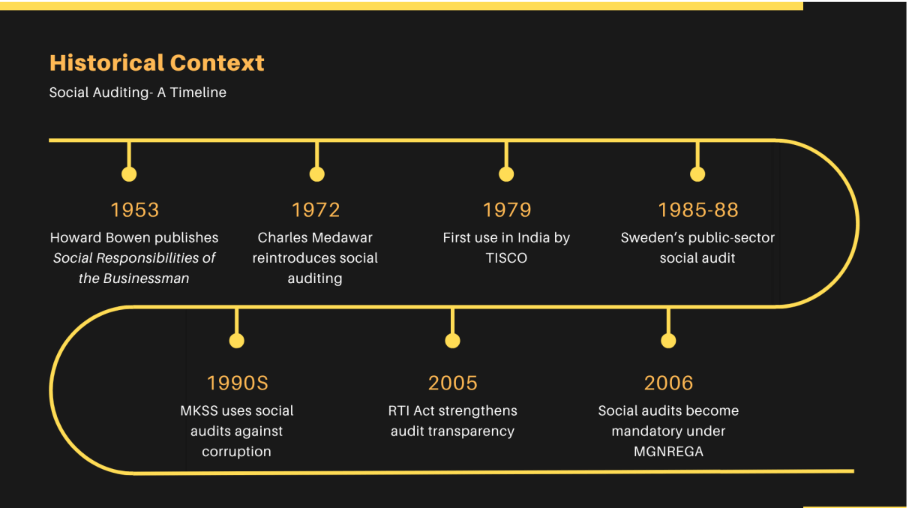

The term “audit” stems from the Latin word audire, meaning “to hear.” Historically, emperors

would appoint individuals to gather public feedback on royal actions—an early form of

community-based accountability. In 1972, British social reformer Charles Medawar

modernized the concept by applying it to corporate and governmental accountability, arguing

that in democracies, decision-makers should act with the approval and understanding of

those impacted.

These principles allow social audits to function as tools for public empowerment, especially

where conventional oversight is limited. They help identify poor governance, corruption, or

neglect, making invisible problems visible.

Globally, the concept evolved in the 20th century. In 1953, Howard Bowen’s book Social

Responsibilities of the Businessman laid early groundwork for corporate accountability.

Sweden’s large-scale social audit (1985–88) became a landmark public-sector example. By

the 1990s, the practice had become more structured, integrating social and ethical metrics

into governance and business alike.

In India, the first known use was by Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) in 1979. The

movement gained momentum through grassroots activism in the 1990s, particularly the

Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) in Rajasthan, which used social audits to fight

corruption. Legislative backing came through the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments

(1992), the Right to Information Act (2005), and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural

Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), which made social audits mandatory for all

projects under the scheme.

How a Social Audit is Conducted

Social audits unfold in two main phases:

Phase 1- Planning and Preparation:

- Establish legitimacy within the community to build trust and ensure participation.

- Identify a focus area for the audit, such as a specific program, service, or policy.

- Obtain relevant government documents and information for transparency and review.

- Form a core group to coordinate the audit activities.

- Mobilize participants from the community, especially the intended beneficiaries.

- Engage relevant stakeholders, including officials, civil society, and interest groups.

- Set dates and arrange logistics for meetings, fieldwork, and public hearings.

Phase 2- Implementation:

- Hold a mass meeting to introduce the audit and establish its mandate.

- Organize participant groups who will be involved in the audit activities.

- Train participants to understand audit tools, ethics, and procedures.

- Develop and test questionnaires to collect relevant data effectively.

- Gather evidence from the community through surveys, interviews, and observation.

- Capture community testimonies and experiences for use in the public hearing.

- Consolidate findings and organize evidence to support key conclusions.

- Prepare for public engagement by planning presentations and discussions.

- Conduct public engagement where findings are shared and debated openly.

- Reflect and follow up on outcomes, recommendations, and corrective actions.

Audits typically examine workforce conditions, diversity, volunteer activities, transparency

levels, salaries, and financial records. They may be public or internal, depending on the

organization’s goals and context.

Benefits and Challenges

Social audits democratize governance by amplifying marginalized voices, revealing

institutional shortcomings, and promoting civic engagement. They enhance an organization’s

understanding of its strengths and weaknesses and improve public image and stakeholder

trust.

However, challenges remain. These include limited access to data, resistance from vested

interests, inadequate follow-up, and the lack of standard procedures. Since many audits are

conducted by non-experts, results can be inconsistent and hard to generalize.

Social auditing is not merely a bureaucratic exercise—it is a people-powered mechanism to

hold institutions accountable. While it faces limitations in execution and enforcement, its

strength lies in its ability to embed democracy into everyday governance. By building

informed communities and responsive systems, social audits can bridge the gap between

policy intent and real-world impact.

In an age where accountability is often outsourced to digital platforms or oversight bodies,

the social audit reminds us of a more grounded truth: citizenship is not passive—it is

participatory.