Author: Harshada Abhyankar

The forests are regarded as the lungs of the planet. With rising concerns for global warming and climate change, it is crucial to look into the Forest Conservation Amendment Act as consented in 2023.

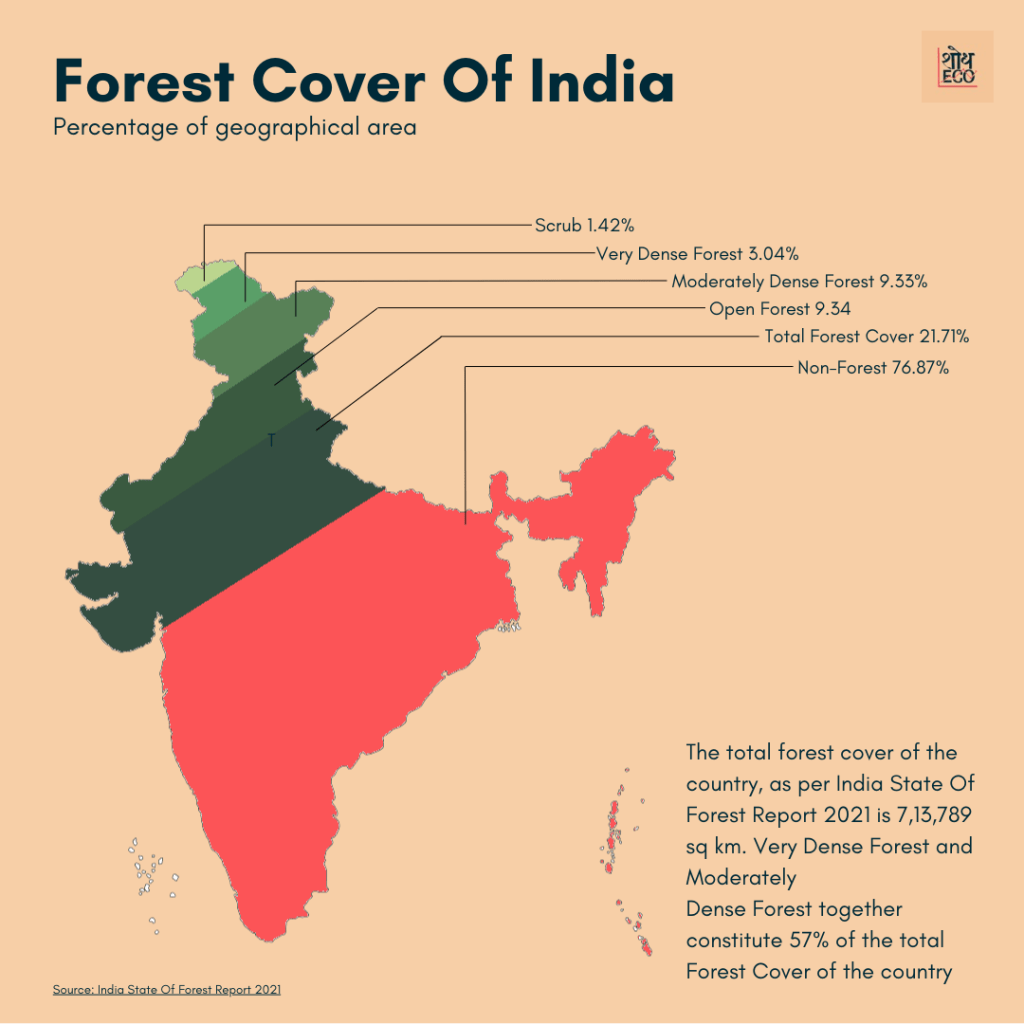

The forests are regarded as the lungs of the planet. With rising concerns for global warming and climate change, it is crucial to look into the Forest Conservation Amendment Act as consented in 2023. The forests act as carbon sinks, temperature regulators, avoid soil erosion and also provide livelihoods to forest dependent communities. As per the Indian survey of forest report published in 2021, 24.62% of India’s geographical area is covered under forest. But studies have shown that there is a loss reported in moderately dense forest. On the contrary, an increase in open forest has been reported. But these forests are ecologically poor hence suggesting degradation of forest ecosystems in India.

In this context, the forest conservation amendment act of 2023 appears as a fright. Since the implementation of the principal act in 1980, 9.83 lakh hectares of forest land has been diverted as reported by MoEFCC. The act primarily deals with dereservation of reserved forest land, use of forest land for non forest purposes and measures of reafforestation. But with the supreme court’s judgement in 1996 (Godavarman case), the equivocacy in identifying forest further proliferated.

To explicate this and suggesting the need for projects of national and international importance, the amendment act was passed. The recent amendment talks about identification of forest land, no clearance required for certain groups of national projects, the land clearance in border areas and left wing extremism affected areas. Certain provisions of the act appear incongruous with India’s climate change mitigation plan. The principal act has been renamed to Van (sanrakshan evam samvardhan) Adhiniyam.

An addition of preamble has been made to the act suggesting India’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2070 and efforts to sequester around 2.5-3.0 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2030. But the amendment has received constructive feedback and dissents of a few from the Joint parliamentary committee set up. The issues pertaining to Amendment deal with ambiguity and wider interpretation of words used in the amendment with regards to identification of strategic projects, no provisions are present for forest enrichment and considering changes in land use only after October 1980.

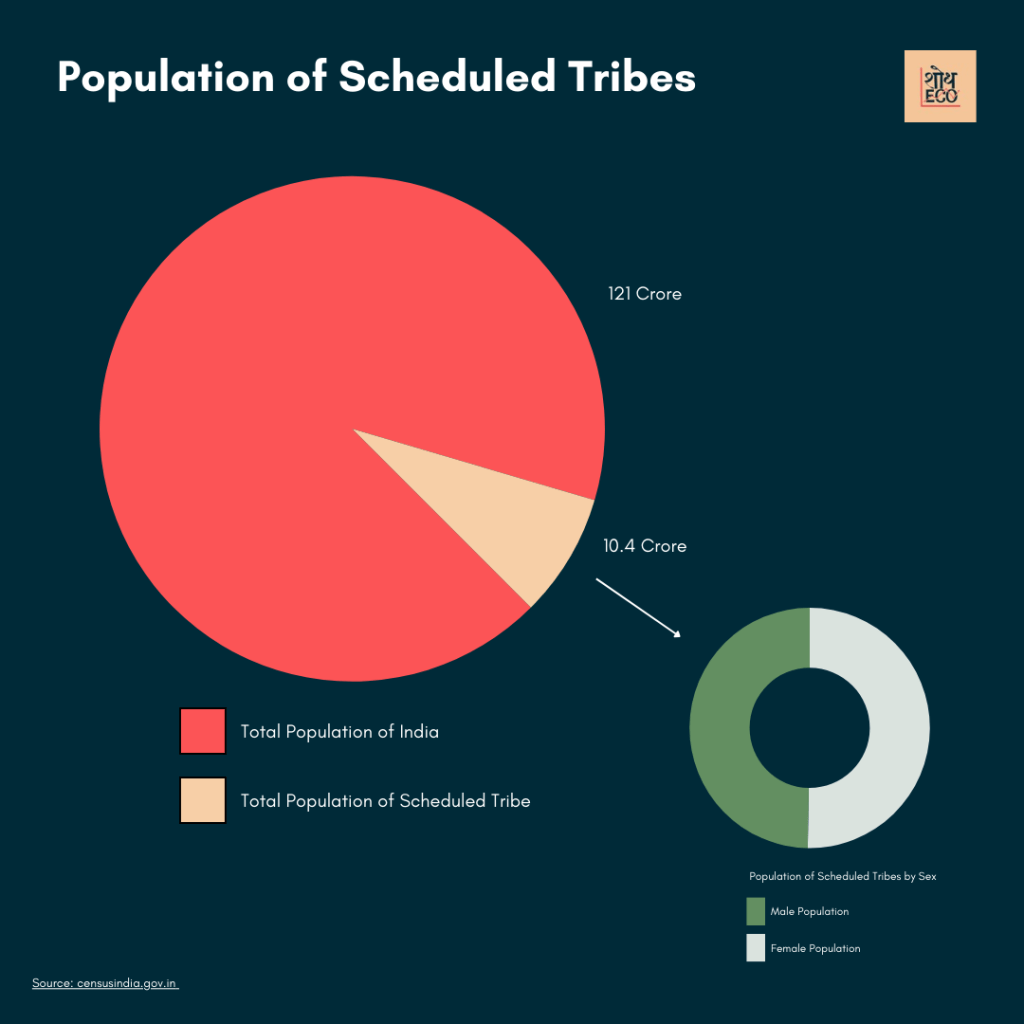

The constraint of 1980 overlooks the land diversions which happened as a result of Zamindari abolishment The amendment also talks about de-reserving area of around 100 km from the border areas for strategic purposes. But this may subsume smaller north eastern states completely such as Sikkim. This will also open up the pristine forest of Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh. This may prove to be a contradictory step with forest survey reporting decrease in forest cover in North East India and fragility of Himalayas.With forest being a concurrent subject, dissenting members of the committee have also stated that the amendment afflicts the federal structure as states consent was not recorded. The amendment needs a redefined approach. With studies stating that by 2030, 45-64% of forests in India will be affected by climate change, greater prudence in climate mitigation and forest enrichment initiatives are required.

The policy issues can be readdressed by using an in depth PESTLE analysis model. This will allow to identify the multiplicity of the issue and stakeholders involved. The accurate mitigation and adaptation policies will substantiate the point to accept climate change, adopt correct strategies and adapt to the change.